Class Six was a challenge to all of us who were teaching them: twenty-seven 10-year olds, all extremely energetic and scattered. Because of their physical energy they were unable to focus their minds and therefore found both individual work and academic work difficult. I had seen that they were more focused on the playing field, and as a yoga practitioner had also seen the benefits yoga could have for children .

The group of teachers working with Class Six came up with the idea of a twomonth experimental intervention to teach them science through yoga practice. I was clear about how to teach topics like the locomotor system, or forces and equilibrium, through the body. But teaching science through yoga practice would not, I felt, be as systematic as in a curriculum module. I also wondered whether it would at all be considered academic learning in science.

For the first few classes I needed about 10 minutes just to settle the students. By the end it took only 90 seconds. They came in and sat down with straight backs, ready to start the invocation.

Part of the focus needed to be on writing, so in the second week I introduced worksheets. Each worksheet contained the following:

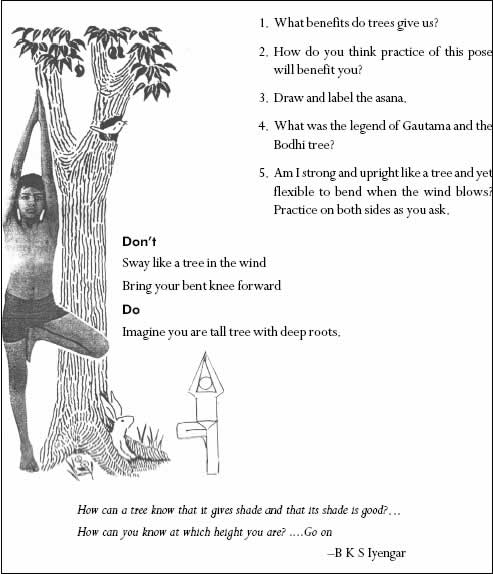

- a drawing of a stick figure in the asana

- a photo of a child performing the asana

- a short list of do’s and don’ts for the pose

- a picture from the story related to the asana

- a list of questions related to the asana that were to be answered

The children were assigned the worksheet as homework the day after the class. I thought it was important for them to try to figure answers out for themselves. In class, I would put them into a pose and correct their alignment. To help extend the time they were able to hold the pose, I would tell a story related to the asana. The story telling turned out to be an important component of the class. Although they were fully engaged in a difficult physical posture while listening, their recall of the events of the story was perfect. Illustrations that I asked them to draw afterwards were very detailed and evocative. They turned out to be an important cultural link to the mythology of the past, something thisgeneration of children is losing out on.

Worksheet questions covered a range of subjects in a non-linear fashion. Some questions related to awareness of the body in the pose (what do you have to do in order to bring your weight to the center? what happens to your trunk as you ‘sit’? which parts of the body do you think this asana strengthens?). Others had more to do with intention or visualization (do you feel like a warrior in this pose? Are you strong and upright like a tree and yet flexible to bend when the wind blows?). Some questions asked the pupil to recount related stories (Gautama and the Bodhi tree, Ravana and Hanuman), to draw and label the asana, or to illustrate the story. Some worksheets asked the children to make a list of wordsdescribing how they felt after the pose.

At the end of the two months we decided to make a presentation for the school assembly. I wanted all of them to participate, not just those who excelled in a particular asana. The preparation was an eye-opener for me. Normally the teacher plans the assembly presentation and oversees weeks of practice. But here I just gave an outline of what we could do and the children selected themselves and filled in for those who were missing. My presence was as a guide. Each child volunteered for one of the asanas: four performed suryanamaskar, then a group did the geometric poses in mirror image with each other, then the remaining children took the animal poses one by one. Our practice was disciplined and cooperative; when role changes were required the children adjusted it among themselves. On the day of the performance, the children made the commentary explaining each pose quite spontaneously.

In the end, it is true that we did not cover as much science as a curriculum module might have. The class enjoyed the sheer physical challenge, and most important, it opened up possibilities of watching and understanding. A number of very interesting lessons were learnt from this experiment:

- The activity was ideal for a large class. In this set-up I was able to attend to each child, and often the instructions that I would give to one to correct the pose were also applicable to many others.

- Being able to give equal attention to each of them brought about full effort in each child. Even the more energetic children were able to focus on the present moment as the activities absorbed them completely. I also found that there was no comparison going on, when each was involved in giving their full effort. Comparison may be a function of disengagement.

- It was very good for those students who might be labeled as slow learners to be able to show a different dimension of themselves.

- It is easier to learn things by memory when they are linked to an activity. Remembering is then supported by various cues.

- The stories were important to show that yoga is not just a set of asanas, but a way of life.

Most significantly, we saw that in the curriculum we often fail to make sufficient time for activities which integrate the mental and the physical. Caught in the requirementsof a timetable, perhaps we give up too easily.