Many traditions over the years have been interested in a way of living grounded in something that is not man-made or created by thought. This way of living is imbued with a quality of flow, an ability to dance with life effortlessly and without a sense of division. A recent description of such a way, albeit in a fictional context, is found in the novel The Wise Man’s Fear by Philip Rothfuss. The author has invented a culture he calls the ‘Ademre’, whose way of life is informed by something called the ‘Lethani’. Here is a conversation between the hero (who is not an Adem and speaks in first person) and Tempi, an Adem who is trying to explain the Lethani to him.*

“What is the purpose of the Lethani?” Tempi asked.

“To give us a path to follow?” I replied.

“No,” Tempi said sternly. “The Lethani is not a path.”

“What is the purpose of the Lethani, Tempi?”

“To guide us in our actions. By following the Lethani, you act rightly.”

“Is this not a path?”

“No. The Lethani is what help us choose a path.”

Does this not remind us of the intelligence that J Krishnamurti talks about? This, too, is a state of being that yields right action, and yet there is no hint of a ‘path’ that leads to intelligence. Through the decades, Krishnamurti remained clear and unwavering on this point, as these quotes from The Awakening of Intelligence illustrate.

“Intelligence is not personal, is not the outcome of argument, belief, opinion or reason.” (p. 385)

“Thought is of time, intelligence is not of time, intelligence is immeasurable.” (p. 420)

“Is there the awakening of that intelligence? If there is ... then it will operate, then you don’t have to say, ‘What am I to do?’” (p. 421)

In Rothfuss’s world, as in traditions such as the wu wei of Taoism, arete of the Greeks, sama-sata in Buddhism or mushin no shin of Zen, it is very clear that what is being referred to cannot be captured in words or understood by the conceptual mind. Apparently, wu wei means ‘non-doing’, and mushin no shin means ‘mind without mind’. However, most of these traditions have some form of practice associated with them, implying that the state of ‘no-mind’ can be achieved as the result of arduous discipline and hard work over time.

Effort, practice and time are of course anathema to Krishnamurti! His logic is impeccable. He clearly demonstrates, and invites the listener to verify empirically that thought is limited, is the source of inattention and, therefore, of the lack of intelligence. Moreover, psychological time and thought are not really different from each other. According to him, “Intelligence comes into being when the brain discovers its fallibility, when it discovers what it is capable of, what it is not.” (The Awakening of Intelligence, p. 385). Unfortunately, thought cannot bring about this perception; thought cannot bring about silence. We cannot use the very things we want to be free of, to become free! And here lies a conundrum.

Krishnamurti felt strongly that the awakening of intelligence is the true purpose of education. Yet no matter how radical our vision of education, we end up creating schools and curricula through which students have a series of meaningful experiences over time—and thought is the currency of most of our transactions. Fundamentally, the education is offered by educators who themselves are deeply conditioned.

How do we get around this conundrum? How should we educators think about it?

Major aim, minor aim

Ironically, some of us who have been attracted to education by Krishnamurti’s questions and his vision of education might not be educators at all if it were not for the possibility of ‘awakening intelligence’. We would agree, I think, to call this our ‘major aim’ of schooling. Yet, as discussed above, this is an aim that cannot be achieved through a programme. If my understanding is correct, intelligence acts when the self is not. And the ending of the self is an act of insight. This insight has no cause and cannot be willed. So what does one do?

If we cannot institute a process, can there be an invitation to the awakening of intelligence? Perhaps our very approach is flawed. For many of us, ‘intelligence’ or mushin are concepts and ideal states that we wish to achieve in the future. Perhaps, as suggested by Krishnamurti, the clue lies in starting where we are with what is observable, and thus, to recognize and understand the lack of intelligence, rather than some positive idea of intelligence. Then the world and ourselves become the laboratory for study and experimentation.

The first step towards the major aim of awakening intelligence is to create the right atmosphere for learning. This demands a relationship based on affection and mutual respect between adults and students. If such a relationship is to be nurtured, it is very clear that we cannot use the traditional motivators of fear, competition, reward and punishment. However, simply having these intentions (and housing the school in serene settings!) is not sufficient. For the atmosphere to have a living quality, there has to be an active exploration of the nature of conditioning and how it impacts daily life. This demands a culture of listening and communication among all members of the community. Dialogue is, therefore, central to such a school. Another mirror to our conditioning is relationship. Very often our deep biases and patterns of response are hidden from our view. We have many blind spots when it comes to ourselves. It is in our reactions to others, in the emotions and thoughts emanating in the theatre of relationship, that our conditioning, our deep sense of being separate, is continually revealed. For relationship to be such a mirror, it has to be imbued with a great sense of compassion, and a renewed realisation that ‘self-knowledge’ does not mean the accumulation of information and images about oneself. If one is not watchful, the network of relationships can end up becoming either oppressive with hurt and conflict, or merely functional, or (worse!) a mutual admiration club.

Creating such an environment is no small order, but let us say we have managed to do so. Now in what ways can we the adults and students investigate the ‘lack of intelligence’? The backdrop for the whole investigation is an understanding of two states of being—awareness and attention.

If I watch myself being angry, I stop being angry. Right? If I watch myself being happy, (laughs) happiness stops. So can you be aware of your movement of thought? This awareness is not identified with thought. Just to watch it, sir, like watching this microphone— watch it. But if I say, ‘It’s a microphone’, it’s that colour, this, who is sitting behind it, who’s talking, I am not watching. So I say, can you watch yourself as though you were looking at a mirror that doesn’t distort? And I said, when there is this alert watchfulness...[it] moves into attention in which there is no centre from which you attend. So when there is complete attention, with your heart, with your mind, with everything you have—to attend—then that intelligence begins to operate.

J Krishnamurti, Fourth Public Dialogue in Ojai, California, April 1977

Again, the question for the educator is how, without creating practices or programmes, can there be an invitation to awareness? Since the ego is rather clever, it can convert anything into an opportunity to enhance itself. Thus, any effort in the direction of becoming attentive or aware can soon become part of a self-enhancement programme, which itself is an impediment to being aware!

Having said this, it still seems important to have certain spaces during the day and week explicitly dedicated to self-learning. We need time for regular dialogue, for teachers and students to patiently unravel their programming, and constantly keep alive the possibility of living without conflict. It also makes sense to have large chunks of time set aside where the whole school does—nothing ! By nothing, we mean no activity, including those that may seem to promote quietness such as reading or listening to music. Everyone is encouraged to be by themselves, alone, not in the company of others. All this is to help us be present, because in the hustle and bustle of daily life, preoccupations and programming take over. A variety of interesting experiments can be tried out during such quiet times, such as noticing how we are constantly thinking of the past and the future, discovering what we are mainly concerned with when we are quiet, why it is so difficult to enjoy the present moment, why it is so difficult to simply do nothing. Perhaps the nature of thought and its structure may unravel itself if we quietly observe?

More and more of our time is being spent in gazing at screens, in a kind of virtual reality. Some psychologists are seriously concerned about a new syndrome they call the ‘nature-deficit syndrome’. In our curriculum, then, it will be important to encourage a relationship with nature and the world of things not constructed by thought. Travel, too, is a way of moving out of the ‘bubble’ we live in. Carefully planned experiences of this kind can be powerful pointers to the crisis we humans face today, and could serve as a catalyst to seeing the cost of our self-centred living.

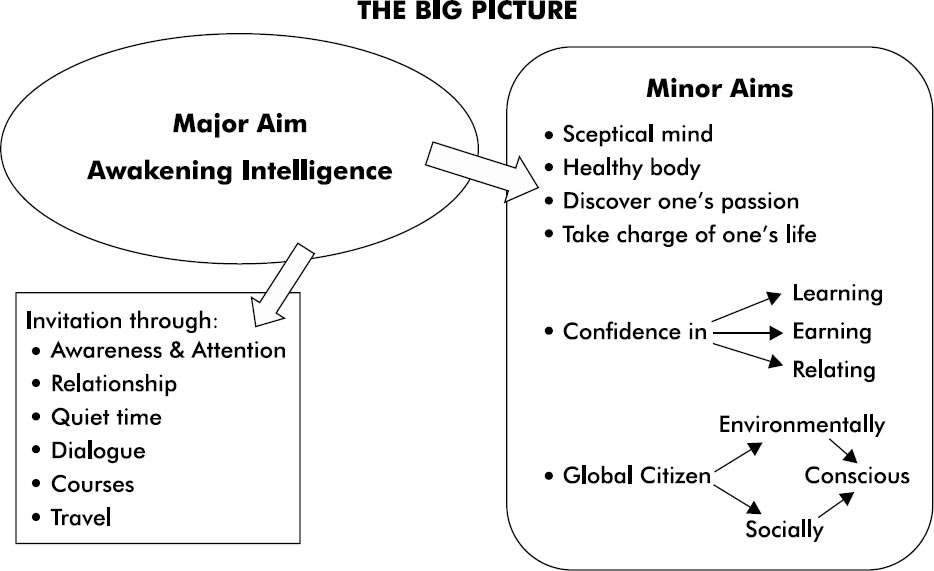

All that I have described above must be at the heart of the curriculum, but the effects of such endeavours are intangible and immeasurable. On the other hand, every school has its nuts-and-bolts curriculum, if I can call it that. We can conceive then of ‘minor aims’, worthy in their own right. One way of understanding the big picture is illustrated in the diagram. I ask for the patience of the purists in this endeavour!

This division into major aims and minor aims is one attempt to answer the question—what exactly is our education attempting to do? Framing the intentions of the school in the above manner provides both a lens to critique what we are attempting to do and also a framework for creative programmes and approaches, especially with regard to the minor aims.

There are two parts to our minor aims. One is to build the ability to live in a complex world, by which we don’t mean merely static knowledge and a set of skills, but rather, the facility to be a flexible and confident learner. Thus, our curriculum should focus more on process than content, building a sceptical capacity in the student’s mind. Also, we ask what it means to help someone find what they love to do in life without constant resistance and worry about security and future.

The other part is to have a world-view which is not divisive. Elements of such a worldview would include a sceptical mind with a global outlook, and which is deeply conscious of the social and environmental crisis facing us today. Obviously for students to apprehend such a worldview, the educators cannot be ‘narrow-minded’; they must be intellectually curious, engaged in understanding themselves and the society that they are a part of.

Once there is clarity in what we are attempting, we can draw upon a variety of resources to translate the minor aims into curricular practice. For example, a school can study its use of resources such as energy and water, and learn about waste disposal. Courses can be designed on wider issues in society such as caste, gender and media literacy. There could be a strong emphasis on intimacy with the natural world in the life of the student. The Journal of Krishnamurti Schools often carries articles describing courses translating philosophy into practice.

What is the relationship between the major aims and the minor aims? I think any educational institution devoted solely to the minor aims can feel that it is engaged in something worthwhile and meaningful. Ideally, if all of us were living embodiments of the ‘minor aims’, then perhaps the world would be a very different place! However, the more we delve into what makes the human world the way it is, and the more we attempt to ‘do something about it’, we encounter a certain fundamental ignorance, a deep lack of intelligence. We are then forced to come back to the whole business of awakening intelligence and the challenges in this realm.

The first and foremost challenge is that the conditioning that the educator, parent and child bring to the table militates against anything that will seriously threaten it! Teachers, like everyone else, try to maintain a certain status quo of seeking security, moving towards pleasure and comfort and avoiding discomfort and pain. Parents may or may not understand the intention of the education and will consciously or subconsciously translate the intentions of the school in the light of their fears and ambitions for their child. Students are a reflection of the society they live in and even though they are far more open than adults, and there is always the great potential for something different to happen, they are strongly influenced by very powerful vested interests.

It seems no matter how well intentioned we are, how willing to pour in a lot of energy and resources into our programmes, how clearly we may think about things, we don’t seem to be making a serious dent in conditioning and how it unfolds. If only ‘intelligence’ can act upon this conditioning, and all our attempts come from the ground of conditioning, we are lost. We cannot purposefully create the ground of intelligence and compassion, and this is the basic conundrum of ‘awakening intelligence’. Let us not move away from this fundamental insight in the daily work of running the school.

* Excerpt from The Wise Man’s Fear: The Kingkiller Chronicles: Day Two by Patrick Rothfuss (2011).