Last November, Oak Grove School welcomed to its beautiful campus both current and prospective families for an All School Showcase and Open House. Teachers took this opportunity to share any one of their class or subject level’s signature projects as a way of demonstrating the power and impact of project-based learning. The school has been involved with project-based learning for a long time, and has increasingly embraced it over the last several years as one way to develop the arts of living and learning at the core of the school’s approach to classroom practice. These arts include inquiry, communication, academia, engagement, aesthetics, and care of/relationship to self, others, and the world.

Why are these arts, particularly the art of inquiry, so important for 21st century learning? While an education based on rote memorization of facts and information may have served previous generations, the sheer volume of constantly changing data available to us today makes this approach to learning problematic—and possibly misguided. While some memorization of core concepts is still important, students today need to know how to access information, synthesize, evaluate, and make sense of it. They need to be practiced at questioning, reflection, challenging assumptions, analysing evidence, and looking at things from multiple points of view.

Many of us are familiar with the old saying ‘Tell me and I forget, show me and I remember, involve me and I understand.’ Well-designed projects have the ability to meet not only the learning goals of the teacher but also the personal interests and passions of students; in other words, to involve students in a way that is truly engaging. Project-based learning moves the student and teacher away from one-answer, standardized facts that must be memorized and towards the formulation of good questions, the exploration of possible answers, the quest for and evaluation of evidence, and the articulation of possible (and probably complex) outcomes. Many of the best projects end up with more questions than they began with!

Well-designed projects have at their core the art of inquiry and farreaching, open-ended wonder. They begin with a driving question or challenge that centres on a significant issue, area of study, or problem. This creates for the student an authentic reason to learn essential content and skills. Guided by the spirit of inquiry, the student begins to acquire knowledge, concepts, and skills that are then applied to the investigation at hand. Interesting, complex questions and challenges require students to step up and engage in higher order thinking and problem solving.

Meaningful projects have embedded within them opportunities for student choice. While a whole class studying American history and literature may be involved in a project focused on The Great Gatsby, the 1920s, and driving questions framed around The American Dream, for example, within the project may be opportunities for individual students to focus on music, clothing, architecture, or prohibition, depending on student interest. One junior-high class project’s driving question was: Through an engaging, handson project that required you to take apart an everyday object, could you learn about energy, natural resources, culture, and the environmental impact of everyday things? This project, called Deconstruct It, had students taking apart computers, iPods, cell phones, televisions and more. While the project had certain criteria and goals set by the teacher, it also allowed for a wide range of student choice and, therefore, engagement.

Engaging students through choice shifts the student from passive recipient to active participant. Students engaged in this way are much more likely to come to lasting and deep understanding rather than superficial ‘forget it after the quiz’ knowledge. Equally important, empowering students with choice and moving them into the driver’s seat of their own education encourages initiative, independence, and responsibility. If we want students to grow up into competent, caring, and responsible members of their communities and the world at large, if we want to grow citizens who will be actively engaged in transforming society, rather than passively accepting the status quo, then we need to give students opportunities in school to exercise their participatory muscles. When I walk into a classroom and see students discussing, fact-finding, questioning, arguing, producing, and problem-solving together, I feel confident that those muscles are getting a workout!

Complex projects usually have at least some component of partner or group work. When projects are designed so that students can only accomplish certain goals via teamwork, students have opportunities to develop and practise important life skills. Contributing to the efforts of a group requires listening attentively to other members of the team, communicating clearly through speech and writing, and learning the art of collaboration. When projects include presentations, especially to authentic audiences, students must develop and practise effective public speaking as well as a variety of technological competencies such as Excel, PowerPoint, film-making, podcasting, model building and web design.

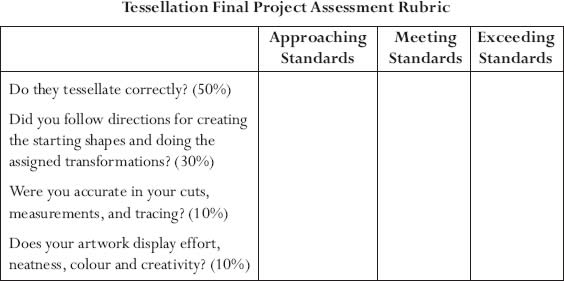

Assessment of projects is an important part of the planning process. Most effective is the use of rubrics with clearly articulated expectations. As most projects are complex, multiple rubrics are usually necessary. Some teachers will, for example, have an ongoing self-assessment rubric, for the individual student and the group or team, that will articulate expectations on processes such as time-management, inter-group communication, collaboration, conflict resolution, and the ability to stay on task. Individual rubrics for discrete components might be necessary—when the project includes a research paper, for example. And finally, there might be a presentation or product rubric for the final outcome of the project.

Oak Grove School geometry students do a Tessellation Project wherein they learn about mathematical transformations (translations, reflections, and rotations) on various polygons that lead to a culminating project of creating M C Escher-type artwork. Students are instructed to design a tile and use it to tessellate at least a half sheet of plain white paper. They then use coloured pencils to create an artistic final product. The students 1) construct a parallelogram or a rhombus and perform two translations; 2) construct an equilateral triangle and perform one rotation about a vertex or construct a rhombus and perform one rotation about a midpoint; and 3) construct a kite and perform a glide reflection. The students are given a rubric to judge their own work as they proceed through the project.

This project not only keeps students highly engaged in mathematics but allows them to integrate their interest in art as well.

But does it work, really? While there is a growing body of evidence indicating that when teachers shift from mainly direct instruction to at least some project-based learning, students produce more intellectually complex work, I would be remiss if I didn’t issue a word of caution! Like other approaches in the classroom, project-based learning can be highly effective or a complete waste of time, according to how thoughtfully each individual project is designed. Teachers must invest considerable time planning ahead to ensure that projects have clear goals and criteria for learning; include student choices and teamwork; and are driven by compelling questions and challenges. Teachers must know ahead of time what students are expected to understand, know, and do as a result of the project, which requires more backward design than traditional lesson planning. In addition, teachers must be available and attentive throughout the process to facilitate, assist, and give feedback.

On the other hand, the potential gains from project-based learning are well worth the time and effort, and are a level risk. A really excellent project may only rise to its potential excellence on the third or fourth try, when a teacher has reflected back and ironed out the kinks.

Project development is often more fruitful and engaging when teachers work to plan them together. At the lower grade levels, this can lead to 15 interesting multi-age projects, allowing mixed-age groups to work together on a common goal. At the upper grade levels, projects allow for collaboration between subject areas—interdisciplinary projects can be particularly compelling for students because they begin to see the interconnectedness of their learning. Common opportunities for integration are between literature and history or mathematics and science, but once teachers start to collaborate, integration possibilities are seen everywhere: mathematics and art, music and history, and so on.

To briefly review: the main goal of project-based learning is not only a product or presentation (although assisting students in the creation of high quality work is important), but also the process of getting there. The process of a thoughtfully considered project encourages students to engage in the act of learning. The students become active, self-directed, and involved participants in this process rather than passive recipients of information. The emphasis is on helping students acquire the skills or arts of inquiry (observation, questioning, fact-finding, research, analysis, self-reflection, and so on), communication (speaking, writing, listening), academia (core content knowledge), aesthetics, and engagement. In addition, project-based learning contributes to the development of participatory citizenship and can empower students to apply these qualities to any of their future interests.

Oak Grove School does not embrace any single educational method to the exclusion of others. Project-based learning is one of a number of teaching strategies that make up the rich palette of possibilities available for our teachers. Well-designed projects in the hands of skilled teacher-facilitators are one way—a very powerful, meaningful, and engaging way—to enrich student learning.